Americans Can Learn from Italy in Preparing for an Age of AI Abundance

Two recent sojourns of mine — one accompanied by my friend and tech entrepreneur Lars Mapstead through the great American west, and the other a personal pilgrimage to my ancestral homeland in northern Italy — have lead me to some rather unexpected conclusions.

Italy is… far enough behind the current social and economic paradigm that, as AI changes the game, it will find itself far ahead of the US in adapting to that change.

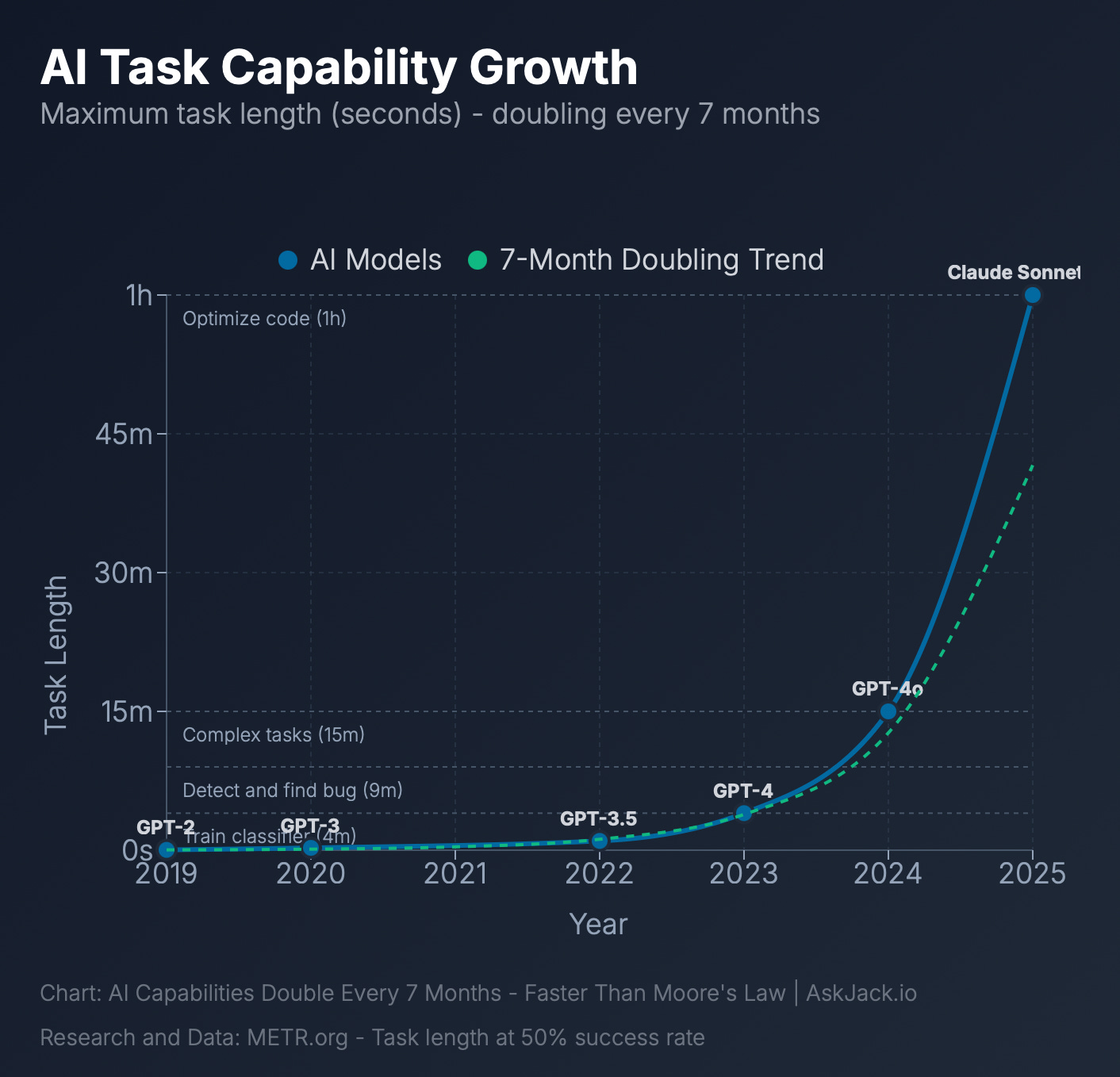

The impacts of the AI revolution are only just now coming into focus, but, with AI’s capabilities better than doubling every 7 months, change is poised to be as quick as it is disruptive. New jobs will not be created at anything near the rate at which current ones will be replaced, and the initial impacts will tend towards those typically more secure from usual recessionary job losses: white-collar professionals, administrators, and middle-managers.

This is a politically dangerous economic cohort. For one, it is huge; 44% of the American workforce is in white-collar jobs. Add to that tradesmen and various other small-businesses, and well over half of Americans are middle class.

Historically in the US, both the most violent turmoil and the most sweeping unrest, can be associated with middle-class discontent. Both slavery and segregation were unpopular with the enslaved and the segregated, but the social change to sweep them away came when the middle class could no longer tolerate such practices. Temperance, too, stemmed from middle class unrest — so it’s not all a record of change for the better. (Looking beyond the US, a decimated and despondent German middle class was a key element of the NSDAP’s electoral coalition in the 1920s and ‘30s).

The American Revolution itself was fueled largely by middle-class discontent (an emerging middle class with the means to exert political and economic will, constrained by a system that fails to provide a mechanism for it to do so, is indeed as volatile as a faltering middle class desperate to retain position and security), and though Southern secession in 1861 was largely an aristocratic pursuit, the Northern abolition movement that was foil to that reactionary sentiment was primarily a middle-class one.

US politicians and pundits should be far more concerned than they are about navigating AI’s disruptive potential. Yet, navigated well it’s a path to the sort of economic growth not seen since the Industrial Revolution. Like the Industrial Revolution, too, the world after will bear little resemblance to the world before.

There’s been much ink spilled already on how Europe’s more comprehensive social safety net primes it both for navigating coming turmoil and joblessness, and gives it a head start building the world of shared growth the AI age will usher in. I won’t rehash that here per se. My travels through Italy, however, have given me a cause to contemplate the social, cultural, and philosophical impacts of a coming AI age of abundance.

The nature of change is such that sometimes one can fall so far behind that they end up ahead. I experienced that personally as Executive Director of the LNC, a third party so far behind the large two that by 2020, when the major parties were scrambling to cope with platforms clamping down on micro-targeting, we found ourselves ahead of the game by never having adopted it enough in the first place to be hurt by the changes.

Italy is similarly far enough behind the current social and economic paradigm that, as AI changes the game, it will find itself far ahead of the US in adapting to that change. Largely, in fact, it’s already there.

For one, the initial wave of white-collar job loss will land with far less impact in Italy. Only 14% of the Italian workforce belongs to that category. As AI replaces even more jobs than that, Italy’s culture of casual labor strikes (my travels were “impacted” by both a general transit strike in which almost no workers actually participated, and a specific Firenze Tram strike that was confined to four hours in the middle of the night while everyone slept) provide the same sort of pressure valve for economic anxiety as elections do for political anxiety.

Further, the economic upside of AI efficiency will likely be even more meteoric in economies like Italy’s where inefficiencies are rife and currently restrain growth much more severely. AI does not keep limited hours, close for months of vacation, allow equipment to wallow unrepaired, or let extractive scams to detract time and energy from the value created by mutually beneficial exchange.

AI will maximize what it is trained to maximize, and do so relentlessly. Italians will disappear for an hour to get a coffee, and that’s their biggest cultural advantage. A world culturally conditioned to define individual value by and through productive labor will face a crisis of the soul in coming years. The Italian soul will be just fine.

“What is it that you do?”

As someone who’s spent a long while now working as an independent contractor, working in politics, performing consulting services, and embodying all the various combinations and permutations of those descriptors, you can imagine there are also periods of time where I find myself not doing much of anything. Contracts and elections end, and new ones don’t always start right up again or afford convenient overlap.

In those moments, it becomes clear to me how much Americans connect identity — both theirs and others — to productive work. Short of “how’s it going,” to which no red-blooded American expects a real answer, the most commonly uttered question in the English language just might be, “what is it that do you do?”

It’s not just that we’re inquisitive about profession either. Even when totally irrelevant to the circumstance, it’s often second only to one’s name when an American has to introduce themselves: “Hi, I’m Bill. I’m an accountant from Omaha with a wife and two lovely kids, and I’ve been collecting stamps now for twelve years.”

Very few people I met in Italy introduced themselves by profession, nor seemed particularly inquisitive about my own. The far more common query, even far from the tourist hubs was, “where are you from?” My horrendous accent likely accounted for some of that, but one also could catch glimpse, in a culture where regionalism weighs on everything from food to custom to family ties, a concept of identity already laden with substitutes for professional identity.

AI will maximize what it is trained to maximize, and do so relentlessly. Italians will disappear for an hour to get a coffee, and that’s their biggest cultural advantage.

What will a post-AI-Revolution America look like? It’ll be recovering from a political upheaval, the result of which will be unpredictable. Economic growth will fuel a system of some sort of basic standard of living for most Americans.

The psychological passion for work — the derivation of one’s purpose from work itself — will be a tough nut to crack, and I’d expect many Americans to cling to their professions long past their usefulness or profitability (usefulness and profitability no longer being strictly necessary to maintain a basic standard of living). Many more will descend into full-time recreation, the skyrocketing demand for content easily met by a mostly AI-generated supply.

Eventually, the fictitious “Bill” will have to find other ways to think of himself — a Nebraskan, a father, a philatelist. His taxes will be done by an AI.

He and every other American will experience something new in the history of our young country. He will no longer be an active builder of the future — we’ll have invented the thing that builds the future for us. He’ll have to learn to live in a world built by others, and in the shadow of the great feats of the past.

What will a post-AI-revolution Italy look like? Like Italy, mostly, just better. Booming GDP growth will solve a persistent problem with public debt, surpluses flowing seamlessly into an existing system of safety nets and support. Pressure valves like strikes may rock the country for a time, but that is hardly likely to alter much the fabric of Italian life.

Inefficient industries will become more efficient. Apps and physical equipment alike (though the distinction between the two will become increasingly murky) will work more reliably. An already expansive system of public transit will become even more accessible, and essentially free.

They’ll still live in the shadow of a past built by Medicis and by Caesars. They’ll still live in a world painted by Leonardos and sculpted by Michelangelos.

The Italian sense of self will persist at peace with the new reality. They will still be fathers and mothers. They’ll still be Italians — still Calabrese, Milanese, or like my ancestors, Lunigianese. The AI Revolution is no greater threat to Campanilismo, the deeply-held affinity for one’s locality, than any prior great upheaval has been.

They will, simply put, still just be themselves. In time, so will we.